For a long time I have marvelled at the elegance of the Ripple protocol, which allows members of a network to extend trust to one another and for payments, or at least virtual payments, to ripple through the resulting mesh along pathways it finds.

Ripple was originally designed as a sort of abstraction of mutual credit. Instead of people forming groups, each account extends a line of trust to several other accounts to form a mesh. Each account is then in its own virtual group. This takes away the mutuality, and effectively puts each user in their own circle.

In Ripple, mutual credit systems can be simulated when an account is created to sit in the centre, and all members trust that account according to an agreed formula and that account trusts them. This was all a bit inelegant and to be implemented with surety would have required some script to be able to control the trust vectors of other users' accounts.

For this reason I stopped asking how we would implement the Credit Commons in Ripple and started dreaming instead about what the credit commons requirements actually were. This was productive because it allowed me to to develop the governance ideas better.

But in recent days I was pulled back to the question. Ripple bypasses the governance problem by letting each user be responsible for their own credit - wouldn't it be much easier just to plug everybody in to Ripple and forget about circles within circles of mutual credit?

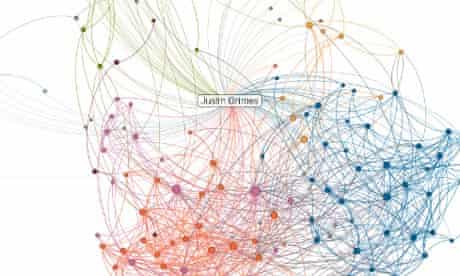

And today the answer came to me. No. Governance may not be needed for individual transactions, but different rules apply accross the network as a whole. Any system of exchange needs a way to manage situations when reciprocation isn't perfect and credit/debt start to clog up the system and reduce liquidity, which eventually leads to defaults. If every Ripple account was equally connected to every other account, as in the diagram on the left, then the onus would be all on individuals to give and receive in equal measure. However in the real world we would expect the network to have clusters of people trading with each other, as in the diagram on the right, and for clusters collectively to have reciprocation issues.

So if my balance is way above zero I may be able to trade it down, but if all my usual trading partners are also approaching their upper limits they won't be able to sell me much. It becomes incumbent on the whole cluster to spend outside the clusters, preferably towards other clusters who are collectively below zero. Ripple provides no way to identify these clusters, so they could communicate or formulate trade policies to solve the problem.

The current credit commons proposal puts each account in one and only one group and invites groups to create meta-groups until payments could go between any two account holders in the same top-level group. This is much more restricting because individual accounts can only be issued credit by members of their immediate group. But it also means that, at each level of grouping, there is a space for policy and relations with neighbouring groups.

With the LETS and timebanks and business barter systems that will be fine, because they already work like that. In the wider economy however, solidarity, self organised groups are rare, which is of course a large part of the original problem!

So I think current fractal design for the Credit Commons is appropriate, but I'm reminded that members will need to be educated about how to use it.

Comments4

"Ripple provides no way to

"Ripple provides no way to identify these clusters".

While Ripple cannot identify clusters directly, it can identify individual account balances. And in the end, it is not a cluster that can spend or receive money, it is only the individuals within a cluster. Unless a cluster governance process decides that the cluster will donate a portion of all positive member balances to another (negative) cluster. Not sure that would work so well.

What are your thoughts on how clusters would manage their excessive positive (or negative) balances?

Member for

17 years 11 monthsBecause clusters are fractal,

Because clusters are fractal, balance limits are managed through a governance process at the next level

Sorry Matt, Still don't get

Sorry Matt,

Still don't get it. Maybe an example will clarify. Imagine that we have defined a maximum level of credit between your cluster and mine. We have hit it and so no additional transactions are possible.

The reason this happened is that one cluster has services the other needs, but not the other way around. Where to from here?

Alexander

Member for

17 years 11 monthsIn a fiscal union the groups

In a fiscal union the groups have an obligation to balance their economies, so they are giving and receiving in equal amounts. That means creditor communities must work with debtor communities to enable counter-flows somehow and to balance BOTH economies. You might think of as a form of solidarity. So this can take the form of creditors making a conscious effort to spend with the debtors, or to invest in the debtors, or failing all that, to donate back to the debtors. Tom Greco gives the example in the Federation of the United States, that the productive states invest in industry and military bases in the less productive states. Exactly this is NOT happening in Europe where there is monetary union but no fiscal union, and Germany's massive budget surplus is NOT reinvested in the Southern states like Greece.